Violence is arguably the most misconstrued issue related to Islam in the Western psyche. Western media has succeeded in linking Islam to violence that now dominates public opinion in the West. Even Hollywood has played a part in promoting global fear and anxiety in their screen portrayal of Islam and Muslims. The Western discourse of “violence in Islam” existed historically from the middle ages, but it has intensified in the past two decades post September 11, 2001 attacks. In the middle ages, Europeans fear of Islam and Muslims has its roots in the Muslims’ territorial expansion that encroached on Christian territories leading to European’s sense of embattled Christendom. Muslims also had their own fear of European domination during Spanish Reconquista and Inquisition of Andalusia. During the 19th century European colonization of Muslim lands, the Western mythical discourse of “violence in Islam” reflected Orientalists’ intellectual distortion of Islam and Muslims to justify policy of domination. New development emerged in the late 20th century with the fall of the Soviet Union that left a political void for the West. Islam became a new geopolitical villain to facilitate West’s foreign policy objectives and domestic interests. At the turn of the 21st century, Western politicians, academia, and media ramped up a new campaign of perpetual “war on terror” in response to September 11, 2001 with preposterous argument that “Muslims are filled of jealous rage against the West”.

This new policy shift is well articulated in 1993 by Harvard University political scientist Samuel P. Huntington who theorized a new phase of West’s geopolitical tension and rivalry which he described as “The Clash of Civilizations” – the term he borrowed from Bernard Lewis’ “The Roots of Muslim Rage” (1990). Huntington positioned Islam, a faith practiced by 1.8 billion people, millions of them in the US and Europe, as being in direct clash with the Western civilization. Like Orientalists who enacted policy on the grounds of Islam and Muslims being an enemy race, the like of Lewis and Huntington lobbied that Islam was not simply a religion, but a rival civilization that needs to be defeated. They constructed an “Islamic Civilization” that was based on essentialist myths and fiction, flawed stereotypes, and most absurdly homogenization of an extremely diverse regions with diverse people and cultures into a reductionist position that Islam was violent, and Muslims were inclined toward terrorism and posed a far greater civilizational threat. The violence perpetrated by a very small number of militant groups with political motivation conjured up in the West the images of religious fanaticism and thirst for vengeance. This flat characterization of Islam and Muslims allowed the West, and the broader “Western Civilization” which they belong, to continue to uphold itself as the bastion of modernity, progress, and liberalism. Revitalizing the principal Orientalist binary of “us versus them” and “they” are everything “we” are not. People like Lewis and Huntington equipped Western halls of power with a new lexicon for analyzing Islam and Muslims that includes, most notably, the phrase “war on terror” and other popular phrases such as “bloody borders,” “civilizational clashes,” “Islamic extremists,” “Islamic terrorists,” “Islamic radicals”, “Jihadists”, “Islamic Fascism”, etc. to explain the Muslim world as they saw it.

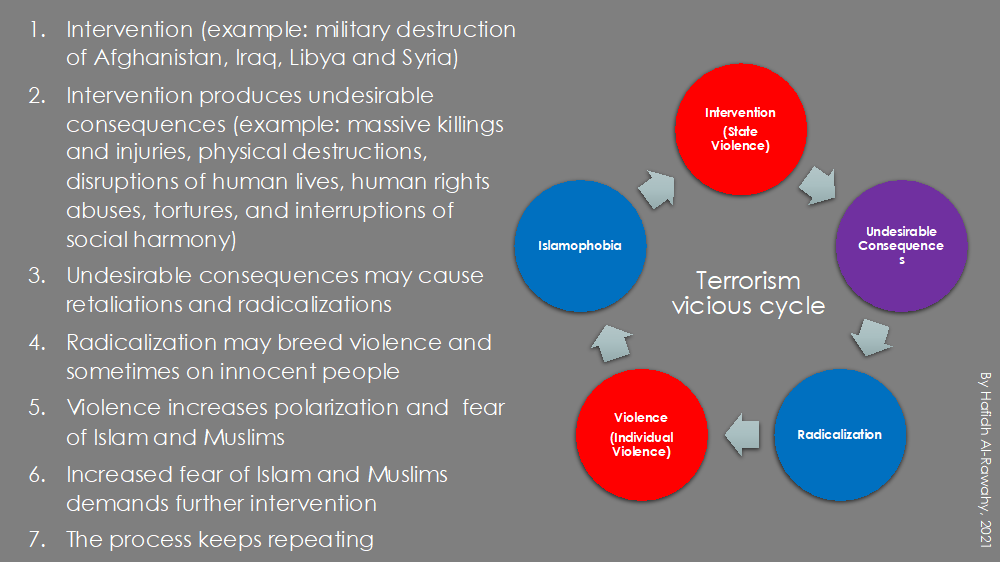

In the West, when one speaks of “violence in Islam”, usually one speaks of “jihad”, the term that appears frequently in the media, academia, and politics, that “seems to encapsulate all the fears evoked by mere mention of Islam and Muslims”. Jihad has become such a familiar word in the Western collective memory that it has entered the English dictionary. For example, Merriam-Webster defines “jihad” as a “holy war” waged on behalf of Islam as a religious duty. The West would rather point to jihad to explain the rise of violence in the Middle East and the Western cities. They avoid the fact that their foreign policy interventions in the Muslim world have been counter-productive, creating terrorism vicious cycle. It seems, there is a clear lack of understanding on the institution of jihad amongst non-Muslims. In the Islamic context, jihad takes three connotations: inner struggle against evil inclinations and carnal impulses, social and religious activism to remove human suffering and improve society, and just war to achieve peace and security against aggressions. The Qur’an uses the word jihad and its derivatives in various contexts, but non as a “holy war”. Recognizing the Creator and loving God more than any worldly thing. Persevering in the face of rejection of faith by unbelievers. Remaining steadfast on the straight path of faith and religious practices. Striving for righteous deeds. Repelling evil with goodness although being tempted to do otherwise. Defending religious freedoms and rights as well as helping allied people who may not necessarily be Muslim. Stopping treacherous people from harming innocent people. Ending religious persecution and stopping the free and open access to Islam. Going to the aid of people who are suffering under tyranny and oppression. Jihad as peaceful religious activism. The Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) also used jihad in contexts far removed from armed warfare. He advised a youth who was seeking to join the army to start his jihad (striving) by serving his parents. “The real mujahid (fighter, striver) is the one who fights (jahada) his own self (nafs) by obeying God’s commands”. When speaking to a man who wanted to know a better form of jihad, the Prophet (pbuh) responded, “a word of truth in front of an oppressive ruler”. “The most excellent jihad is the Hajj”. In modern secular societies where consumerism, self-interest, carnal desires are highly regarded, it is a challenge to lead a God-conscious life, to remain ethical, and to be faithful to your faith. Jihad, in this case, is a constant struggle for Muslims to remain God-conscious as individuals, families, and communities as Fethullah Gulen beautifully articulate, “Jihad is removing obstacles between God and the human”.

In the West, when one speaks of “violence in Islam”, usually one speaks of “jihad”, the term that appears frequently in the media, academia, and politics, that “seems to encapsulate all the fears evoked by mere mention of Islam and Muslims”. Jihad has become such a familiar word in the Western collective memory that it has entered the English dictionary. For example, Merriam-Webster defines “jihad” as a “holy war” waged on behalf of Islam as a religious duty. The West would rather point to jihad to explain the rise of violence in the Middle East and the Western cities. They avoid the fact that their foreign policy interventions in the Muslim world have been counter-productive, creating terrorism vicious cycle. It seems, there is a clear lack of understanding on the institution of jihad amongst non-Muslims. In the Islamic context, jihad takes three connotations: inner struggle against evil inclinations and carnal impulses, social and religious activism to remove human suffering and improve society, and just war to achieve peace and security against aggressions. The Qur’an uses the word jihad and its derivatives in various contexts, but non as a “holy war”. Recognizing the Creator and loving God more than any worldly thing. Persevering in the face of rejection of faith by unbelievers. Remaining steadfast on the straight path of faith and religious practices. Striving for righteous deeds. Repelling evil with goodness although being tempted to do otherwise. Defending religious freedoms and rights as well as helping allied people who may not necessarily be Muslim. Stopping treacherous people from harming innocent people. Ending religious persecution and stopping the free and open access to Islam. Going to the aid of people who are suffering under tyranny and oppression. Jihad as peaceful religious activism. The Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) also used jihad in contexts far removed from armed warfare. He advised a youth who was seeking to join the army to start his jihad (striving) by serving his parents. “The real mujahid (fighter, striver) is the one who fights (jahada) his own self (nafs) by obeying God’s commands”. When speaking to a man who wanted to know a better form of jihad, the Prophet (pbuh) responded, “a word of truth in front of an oppressive ruler”. “The most excellent jihad is the Hajj”. In modern secular societies where consumerism, self-interest, carnal desires are highly regarded, it is a challenge to lead a God-conscious life, to remain ethical, and to be faithful to your faith. Jihad, in this case, is a constant struggle for Muslims to remain God-conscious as individuals, families, and communities as Fethullah Gulen beautifully articulate, “Jihad is removing obstacles between God and the human”.

Bibliography

Lyons, Jonathan. 2012. Islam Through Western Eyes: From Crusades to the War on Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ramadan, Tariq. 2017. Jihad, Violence, War and Peace in Islam. Swansea: Awakening Publishers.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. 2015. The Study Qur`an: A New Translation and Commentary. New York: HarperOne.

n.d. www.sunnah.com.

Beydoun, Khaled A. 2018. American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear. California: University of California Press.

Esposito, John L., and Ibrahim Kalin. 2011. Islamopbia: The Challenges of Pluralism in the 21st Cnetury. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Esposito, John L. 1999. The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Etiene, Bruno. 2007. “Islam and Violence.” History and Anthropology 18 (3): 237-248.